Culture Desk

By Lauren Collins

Toussaint Louverture, according to the scholar Sudhir Hazareesingh, was “the first black superhero of the modern age.”

Louverture was born enslaved on a sugar plantation on Saint-Domingue, a French colony on the island of Hispaniola, sometime in the early seventeen- forties. He was emancipated in adulthood and, at about fty, led the most important slave revolt in history, effectively forcing France to abolish slavery, in 1794. Next, he united the island’s Black and mixed-race populations under his military command; outmaneuvered three successive French commissioners; defeated the British; overpowered the Spanish; and, in 1801—despite having been wounded seventeen times in battle and having lost most of his front teeth to a cannonball explosion—authored a new abolitionist constitution for Saint-Domingue, asserting that “here, all men are born, live, and die free and French.” Napoleon Bonaparte rst sent twenty thousand men to overthrow him, reinstating slavery in the French colonies, in 1802. Louverture instructed Jean-Jacques Dessalines to torch the capital city, “so that those who come to re-enslave us always have before their eyes the image of hell they deserve.” Ultimately taken captive, Louverture was deported to France and died within months in a prison in the Jura

Mountains. In 1803, Bonaparte’s army was defeated, having lost more soldiers (his brother-in- law among them) on Saint-Domingue than he would, twelve years later, at Waterloo. The next year, the revolutionaries established a new, independent, and free nation: Haiti, the world’s rst Black republic.

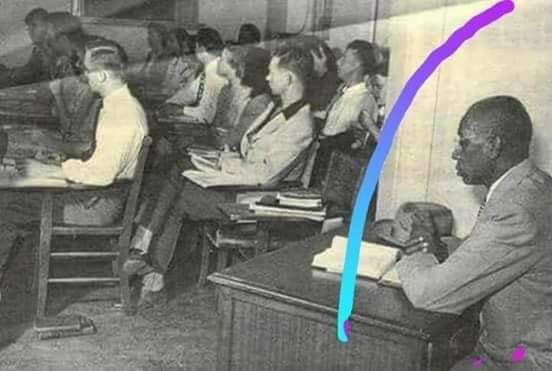

For the moment, a typical French student completes her high-school education without hearing

much about any of this. Despite Marcus Garvey’s assertion that Louverture’s “brilliancy as a

soldier and statesman outshone that of a Cromwell, Napoleon, and Washington,” despite Aimé

Césaire’s belief that Haiti was the place where “negritude stood up for the rst time and proclaimed its faith in its humanity,” despite the fact that Louverture—hailed as “the Black Spartacus,” hero of Frederick Douglass—embodied the ideals of the French Revolution and, then, the Haitian Revolution, which inspired the modern anti- colonial movement all over the world, France has not seen him and his ght as indispensable elements of its national narrative. “It’s thought of as a minor story, not la grande histoire,” Elisabeth Landi, a history professor in Martinique, said. In 2009, an inscription honoring Louverture was engraved in a wall at the Pantheon. The story of his country’s revolution is taught in high schools in some of France’s overseas territories. In metropolitan vocational high schools, whose students are more likely to come from working-class and immigrant families, the recently updated curriculum acknowledges the Haitian Revolution as a “singular extension” of the American and French revolutions. But it is not mentioned in the general lycée curriculum. A future pipe tter in Paris will thus know that enslaved Black people in a French colony sought and secured their own freedom, but an aspiring politician, having done all her homework at lycée, may understand emancipation simply as a right granted in 1848, by decree of the Second Republic.

Lauren Collins has been a staff writer at The New Yorker.